What's on Display: Shop environments in the work of Wayne Thiebaud, Claes Oldenburg, and Tschabalala Self

Wayne Thiebaud’s work has long been framed, in one way or another, in relation to pop art. While he has frequently been linked to this movement due to his depiction of everyday subjects, there has been a consistent critical resistance to this categorisation. Demonstrating this dynamic of contrasts, his work was exhibited in the landmark 1962 pop exhibition “New Painting of Common Objects,” which included works by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. Even then, a contemporaneous Artforum article by John Coplans singled out Thiebaud as an anomaly within the group. He wrote:

“The sense of crisis precipitated in Lichtenstein’s painting is totally missing in Thiebaud’s paint act; Thiebaud’s art is a coincidence: he lacks the guts and the total commitment of the others in this group… The anguish of the situation is not well enough reflected; he titillates rather than creates a distillation that can either lead to, or bare the heart of the issues.”

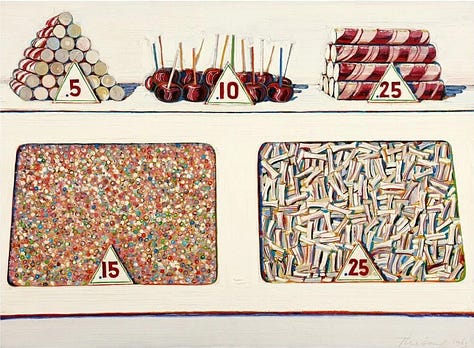

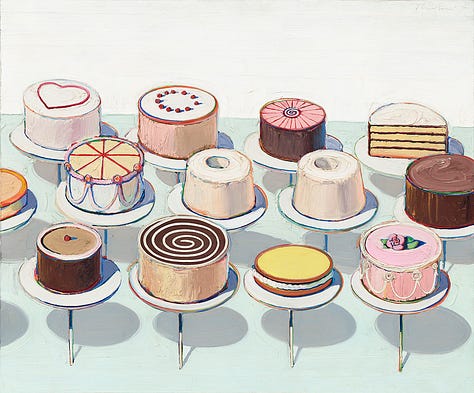

Coplans’ cutting critique points to one of Thiebaud’s key points of differentiation from his pop contemporaries, which Coplans chooses to frame as a shortcoming but is more fairly understood as a divergence in approach. The main cohort of pop artists were critically exploring concepts of consumerism and the expansion of the postwar middle class, often employing imagery that amplifies these themes or using processes that emulated mass production. While artists like Warhol and Lichtenstein pursued the stark uniformity and repetition of manufacturing, Thiebaud sought to investigate subtle points of formal difference within that visual sameness through studies everyday subjects. His painterly focus on the objects led him to use thick, expressive strokes, at times recreating the effect of toppings in his application of impasto. This difference in approach is evidenced by his citation of artists like Cézanne as part of his artistic lineage.

Here, I would like to consider Thiebaud’s work alongside that of his contemporary Claes Oldenburg, who’s 1961–2 installation The Store provides an excellent point of comparison for how these artists dealt with similar imagery towards different thematic ends. Later, I will come forward in time to explore how Tschabalala Self’s 2017 installation Bodega Run approaches this subject from yet another perspective, engaging with issues of class and race.

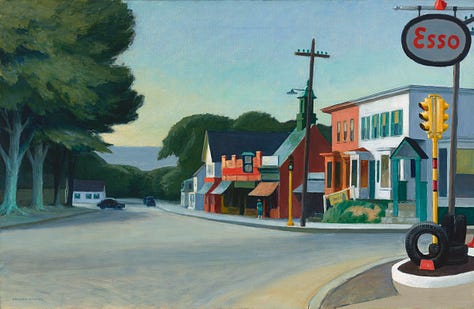

Thiebaud’s work simultaneously manages to be visually tempting in its subject matter yet uninviting in its pristine presentation. Aside from the life-size scale of some paintings, which could facilitate an immersive effect, the viewer is not exactly invited into the scene. The food is untouched, the surfaces are immaculate, and there are no figures present to activate the space as either the consumer or as a salesperson counterpart to the viewer. The perfection in the images makes it feel that they are not for the viewer—they are display only. There is a promise of something that is never delivered, and this evokes romanticised ideas of an American dream that will never materialise for many who aspire to it. Visually, the shadows are harsh, as one might see in a staged film scene or photograph. This manner of display, coupled with the isolated feel of the works bears a kinship with Hopper’s representations of America, with depictions of empty cities and melancholy figures. That wistfulness can also be observed in Thiebaud’s paintings, such as Peppermint Counter (1963), which evokes a bygone era through its reference to the penny candy bins of the artist’s youth.

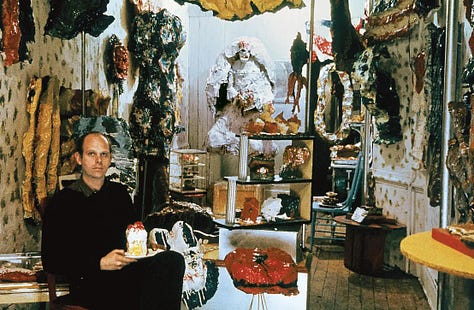

Let us contrast these works with sculptures from Claes Oldenburg’s The Store (1961–2). Pastry Case I (1961–2) is filled with shining painted pastries with lumpy textures and slightly unnatural colours. The case and the plates are objects that would actually be used in a deli, and yet, the overall effect of what is presented is a grotesque caricature of what one would really encounter. Where Thiebaud’s pastries look good enough to eat, Oldenburg’s provoke hesitation. In another crucial difference, Oldenburg’s pieces were activated by the viewer in their original installation presentation. The artist filled a downtown Manhattan store with sculptures of common items and operated it like a shop. He served as the shopkeeper and people were able to purchase from the displays. In visiting The Store, ‘viewers’ and ‘collectors’ became ‘browsers’ and ‘shoppers,’ and were thus subsumed into the installation experience. The value of Oldenburg’s experiment did not lie strictly in its novelty, but also in his democratisation and deglamorisation of the art buying process, rendering it a more mundane and transactional experience.

In a text from ‘Documents from The Store,’ Oldenburg wrote that America is ‘bourgeois down to the last deathtail,’ and argued that art criticism championed bourgeois values. He aimed to challenge this by making ‘charged’ objects, not capital-A ‘Art,’ rejecting the sanctity of the gallery in favour of the banality of a retail space. Towards this aim, he placed his objects in a store, which he defined to as ‘a place full of objects’ as of asserting their places as objects.[1] We can see how, both, Thiebaud and Oldenburg focus on the objects and champion everyday subjects, but Oldenburg does this to challenge inherent value systems within what he views as a bourgeois scene. Where Thiebaud’s work is a study of objects, Oldenburg’s is therefore more convincingly understood as a study of social behaviour via objects. In situating these works a shop context, he also comments on the underbelly of growing consumerism at the time. His Pepsi-Cola Sign (1961) featured in the shop embodies this well, where the artist presents a grotesque version of a well-known brand and common shop fixture.

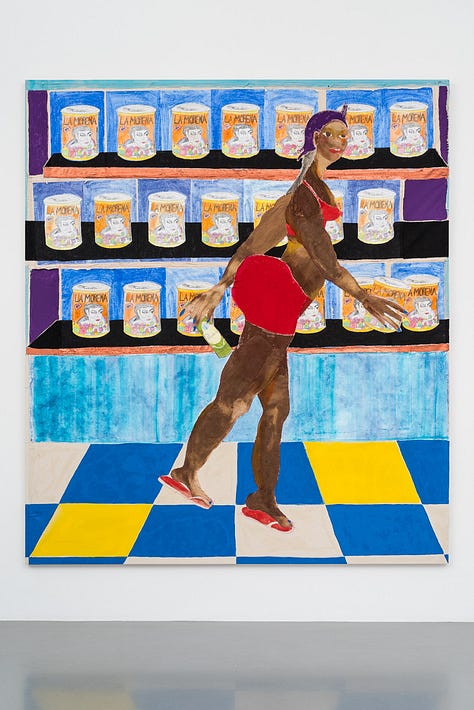

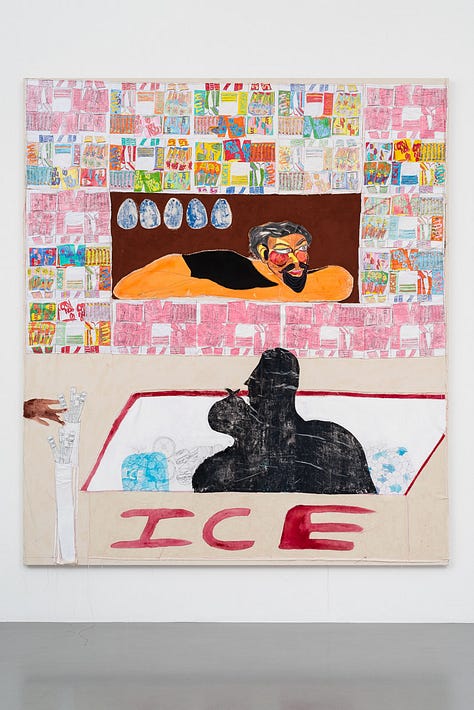

Moving to Tschabalala Self’s 2017 Bodega Run installation, we see a more contemporary exploration of the shop environment. Self, who grew up in Harlem, bases the installation on the bodegas found throughout New York City, particularly in Black and Brown neighbourhoods. Named from a Spanish word for ‘store,’ bodegas were first established by Puerto Rican and Dominican communities in the 1950s. The shops are known for having a resident cat, and Self prominently displays two large plywood cat sculptures in the middle of the installation area. Other theme-appropriate elements include milk crates and wallpaper depicting rows of products. In the wall-mounted works, Self takes a pop art approach by depicting brands commonly found in these shops, such as Tide laundry detergent, Scott toilet tissue, and culturally specific offerings like Goya beans and La Morena pickled jalapeño peppers.

Where Oldenburg’s store was activated through viewer engagement with the objects, Self’s mixed-media works depict figures in context, with the wider installation also inviting the viewer in as participant. She shows the communities who shop within these spaces as well as the owners who operate them, foregrounding the social dynamics that structure everyday exchanges. The artist has said that one of the aspects that intrigues her about these spaces is the dialectical tension that exists between the shop owners and customers, where they want patronage while also mistrusting their clientele.[2] She represents this by mounting the same type of convex security mirror that is used to monitor customers in one corner of the gallery. Bodega cashiers are often behind protective plexiglass as well, and Self alludes to this by employing that material in her Keeper figurative pieces. Oldenburg’s store mocks consumer culture by inviting customers in to participate in a kind of farce, but Self’s highlights the hypocritical social politics of spaces where customers seem to be, both, welcome and kept at a distance.

Thiebaud and Oldenburg’s works belong to worlds of excess and access, where Thiebaud presents an abundance of unattended treats and Oldenburg facilitates tongue-in-cheek transactions with a bourgeois audience. Moreover, the foods depicted by both artists are largely non-essential, pleasure-oriented items. There is a sense of plenty underlying these works; they occupy worlds of expendable income and luxuries. Self’s bodega environment, by contrast, centres a place in which many carry out their primary food shopping as well as buying snacks. Some bodegas are the only grocery options within food deserts and offer limited options for fresh or healthy food; this disproportionately affects low-income communities, with food poverty in the United States falling most heavily on Black and Hispanic households.

These artists invite viewers to engage with the visual culture of food shops as embodiments of wider societal patterns, touching on popular foods, consumer behaviour, and issues surrounding class and race. Explored together, these works demonstrate how the shop functions as a mutable cultural site and as a charged social space.

This paper was originally presented at Research Notes: Wayne Thiebaud’s American Still Lives for The Courtauld Centre for the Art of the Americas on 15 January 2026.

[1] Claes Oldenburg, “Documents from The Store,” in Art in Theory 1900-2000, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, New ed., 743-747 (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 744.

[2] Ferren Gipson, Women’s Work: From Feminine Arts to Feminist Art (London: Frances Lincoln, 2022), 200.